Sarah-Hope has asked me if I would write an occasional blog entry about art. This past weekend I took part in Roadworks at the San Francisco Center for the Book, so now is a perfect time to write my first Art Talk entry.

The San Francisco Center for the Book is a great resource. They not only offer classes in printing, bookbinding, letterpress, block printing, and other related crafts, they have a small gallery in which they display books and book-related art. Their current exhibit is “Banned and Recovered: Artists Respond to Censorship”, in which 50 artists respond to threats to intellectual freedom, past and present. (And more on that later!)

Roadworks is an annual fundraiser and street fair organized by the SFCB, during which they make giant linoleum block prints using a steamroller as a printing press.

I have to say, using a steamroller to make prints is absolutely brilliant. I think all printmakers have a bit of the gadget geek in them; you make art using knives, scrapers, acid baths, light boxes, barens, printing presses, and so on. So we all drooled over the rumbling rollingness of the steamroller, fantasizing over keeping one parked in our own backyards.

The gadget geekiness spills over into the craft of printmaking. Not only do you use specific tools in order to make a print, you need to follow a complete process that is painstaking and usually time-consuming. The photos I took at Roadworks illustrate the process of making a block print. Even though the scale is much larger than usual, the steps are the same. (Knitting is a mystery to me, and I often find printmaking is a mystery to knitters. If this is all old news to you, skip to the bottom of my post.)

After drawing your image and carving it into the block –that’s another story!– the artist needs to ink the block. For Roadworks, a group of 6 artists was invited to carve 3-foot-square linoleum blocks, and random local artists (like me) could volunteer to carve smaller 1-foot-square blocks. This picture shows volunteers inking one of the large blocks. Ink is rolled out on a plexiglass plate using a rubber brayer, which is then used to roll the ink evenly over the surface of the block.

Here is a picture of one of the large prints after it’s been printed:

For steamroller printing, inked blocks were laid down in a grid on top of a piece of plywood:

Even with a small press, you need to protect the paper (and block) from the pressure used to make the print. When you use a steamroller, you stack up several blankets and a hunk of carpet and lay them on top of the blocks.

Then stand back! Here comes the steamroller over the princess-and-the-pea stack of blocks, paper, and blankets!

The moment of truth. The blankets are lifted off, and volunteers –the “clean hand” crew– peel the paper off the inked blocks.

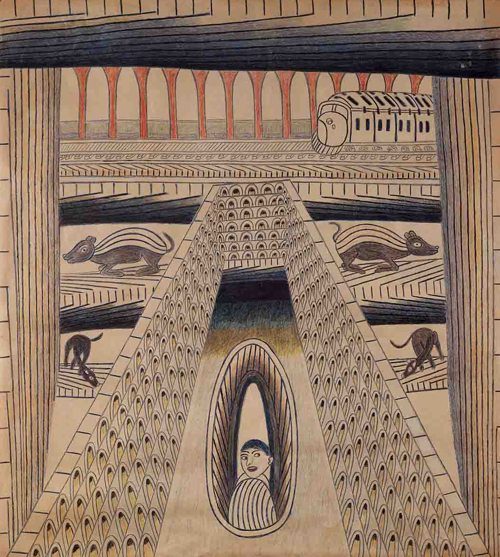

And here is my print, hot off the press:

In keeping with the larger theme of books, book arts, and banned books, I decided to make my “little lino” a piece about current events, specifically, the presidential race, and even more specifically, the story about Sarah Palin trying to dismiss the Wasilla town librarian after she refused to take some “offensive” books off the library shelves. The print is called “Open Season”, subtitled “In Which Sarah Palin, Far to the Right, Enjoys Taking Out Some Library Books.”

Shameless commerce department: In keeping with the fundraising spirit of Roadworks, I’m putting this print to some good use. I’m selling signed original prints on Etsy, with 50% of the proceeds going to the American Civil Liberties Union. And I’ve also put it on shirts, tote bags, and print items (note cards, etc.) on Cafe Press, with 100% of my profits from them also going to the ACLU. (While you’re there, also check out my “No on 8” products, which urge California voters to support same-sex marriage in November. Proposition 8 would change California’s constitution to specifically ban gay marriage.)

Art, books, politics; it’s a fine mix and made for a wonderful afternoon. Using my little hand press in my garrett will seem somewhat mundane after this!

[Guest blog by Melissa]