Mmmmmm. Before we do anything else, check out this yarn.

It’s from Cathy-Cate at Hither and Yarn. I won this prize for being the 100th commenter on her blog. I had no idea there was even a competition going on! She sent me the nicest note, congratulating me and asking about my taste in yarn. I told her I like rich colors, and she wrote back to say, “I have just the thing.” Well, this yarn most definitely is just the thing. It’s a 140-yard skein of wool-silk blend with a real sheen to it (the photo gets the colors right, but doesn’t reproduce its luster). I don’t know yet what I’m going to make with it, but this skein definitely deserves to have a new pattern written it its honor—perhaps some decorative, but functional wrist warmers?

As I promised, here’s a picture of the dishrags I knit up using self-striping Sugar ‘n Cream.

The cloth on the left uses the self-striping yarn as the background; the cloth on the right uses it as the “ribbons” that run across the piece.

Melissa and I spend most weekends together, but occasionally life interferes, as is the case this weekend. She needs to spend most of her time up in Oakland carving lino-blocks for her upcoming shows; I need to stay in Santa Cruz to protect the homestead from ravening herds of raccoons. So, in lieu of a weekend’s domestic bliss, we met up in San Jose for a date.

We both love this statue of the feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, that stands guard at the plaza set among the city’s museums and theaters.

After a delightful lunch at the Old Spaghetti Factory (bless Melissa for her willingness to indulge my love of mizithra!), we walked to the San Jose Museum of Art, which is hosting an exhibit of the works of MartÃn RamÃrez.

The museum documentation offers a brief summary of his life story:

RamÃrez (1895–1963) created some three hundred artworks of remarkable visual clarity and expressive power within the confines of DeWitt State Hospital, in Auburn, California, where he resided for the last fifteen years of his life. He had left his native Mexico in 1925 with the aim of finding work in the United States and supporting his family back home in Jalisco, but the economic consequences of the Great Depression left him homeless in northern California in 1931. Unable to communicate in English and apparently confused, he was diagnosed as a schizophrenic and spent the second half of his life in mental institutions.

In the 32 years he was institutionalized, RamÃrez hardly spoke to anyone but taught himself to draw. Tarmo Pasto, a professor of psychology and art at Sacramento State University, discovered RamÃrez’s drawings in the early 1950s. Pasto started to supply RamÃrez with materials and eventually collected his drawings and organized public exhibitions of his work.

MartÃn RamÃrez’ oeuvre forms an impressive map of a life shaped by immigration, poverty, institutionalization, and most of all art. Migration and memory seem to factor strongly in his images, which document his life experiences; favored images of Mexican Madonnas, animals, cowboys, trains, and landscapes merge with scenes of American culture. While his singularly identifiable figures, forms, line, and palette reveal an exacting and highly defined vocabulary, they also show RamÃrez to be an adventurous artist, exhibiting remarkably creative explorations through endless variations on his themes.

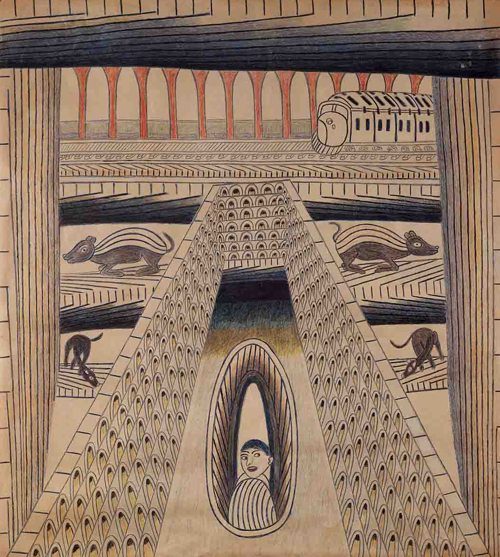

The mix of beauty and playfulness in this piece drew an involuntary little gasp from me as I turned to face it.

As you can see in this image, his works are quite large and done on multiple sheets of paper pasted or taped together.

Melissa and I wondered whether this was by choice or if he was only supplied with the small sheets and did the joining up out of necessity. We also wondered whether he drew first, then joined or vice versa. Because he was viewed as an interesting psychological case, rather than as a full-fledged artist, during his life, his artistic process seems not to be well documented.

One of the most enjoyable features of the San Jose Museum of Art is the reading area attached to each exhibit, with comfy chairs and books about the featured artist and related works. We looked through the exhibit catalogue and decided we’d have to buy a copy of it. We also fell in love with another book, Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States. Unfortunately, the museum didn’t have this book for sale, but we’ll be tracking down a copy as soon as we can.

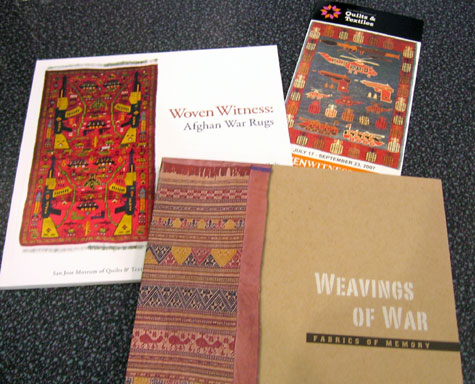

We made our second stop at the San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles, which currently offers several exhibits of textiles exploring themes of war and human rights.

“Woven Witness: Afghan War Rugs and Afghan Freedom Quilt” looks at the way traditional Afghani rug making has been altered to incorporate images of military conflict.

These images began to appear in Afghan rugs, at first in “hidden” form, shortly after the Soviet Invasion in 1979 and continue to appear—modified to reflect changing politics and conflicts—today.

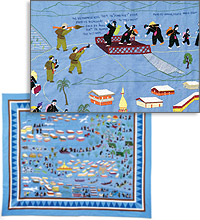

The traveling exhibit, “Weavings of War: Fabrics of memory,” includes pieces from many cultures.

This Hmong story cloth documents Hmong collaboration with U.S. forces in Vietnam, their subsequent persecution, escape as refuges, and immigration to the U.S. The exhibit also included two large quilts and several smaller pieces documenting life under apartheid in South Africa, small works in appliqué from Chile and Peru documenting human rights abuses, and traditional Asian weavings with military motifs incorporated, along with a number of other kinds of pieces.

I feel insufficiently wise to explain what viewing these pieces meant, the messages they spoke, and the ways they made me contemplate what it means to be an American living the life that I do. The scope of the violence and suffering is so broad and has so many causes that I could easily feel helpless in the face of it all. But these pieces of handwork remind me of the power of individual actions. Perhaps one of the lessons is that I shouldn’t waste my time trying to decide upon the most effective, most comprehensive action. Instead, I should focus right now on the things I do every day, the activities I love, and work to make them part of my own response to the injustices around me.